Touchstone

Talking to the Planet in a Pebble – Using CWTP as a Regenerative Resource During the Anthrobscene

Mark Smalley

Climate News Tracker

Abstract

Touchstone investigates what happens when the man-made climate and nature polycrises—what I call the Anthrobscene—is approached through the lens of geological deep time using established creative writing for therapeutic purposes (CWTP) techniques to enable a conversation between us and rocks. Does such an encounter have any distinctly regenerative, therapeutic benefits? Feedback from my two co-researchers and seven workshop participants confirms that it does. This paper explores how and why this may be. The Touchstone approach is underpinned by Joanna Macy’s influential The Work That Reconnects (TWTR) for activists and an action research methodology. This is combined with creative writing and the growing evidence-based insights that confirm the health benefits of people reconnecting with nature together outdoors. Touchstone confirms that participants can feel consoled and inspired when given the opportunity to develop a close, inquiring relationship with stone while engaging with, writing about, and reflecting on rocks. The process, I suggest, enables us to glimpse over the vertiginous cliff edge of these bewildering times while regrounding ourselves in pre- and post-human timescales that enable us to continue the fight for all life and for sanity.

Keywords: deep time, geology, creative writing for therapeutic purposes, Anthropocene, climate and nature crisis, rocks

APA citation: Smalley, M. (2024). Touchstone. Talking to the planet in a pebble – Using CWTP as a regenerative resource during the Anthrobscene. LIRIC Journal, 4(1), 52–98.

Touchstone

Oolooks and oolites

light the stony path to

knowing my not knowing,

a riddle composed of warm

touchstone, cold headstone

and, in between, a hearthstone

whose gritty bits

rattle down

through

my

rainstick

life

(Smalley, 2023)

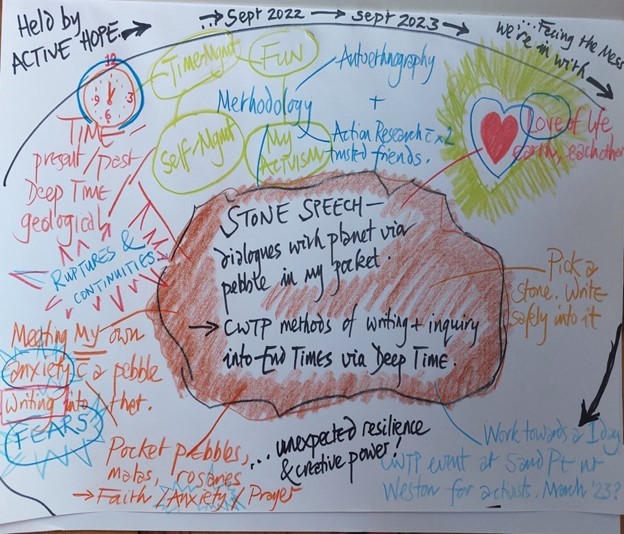

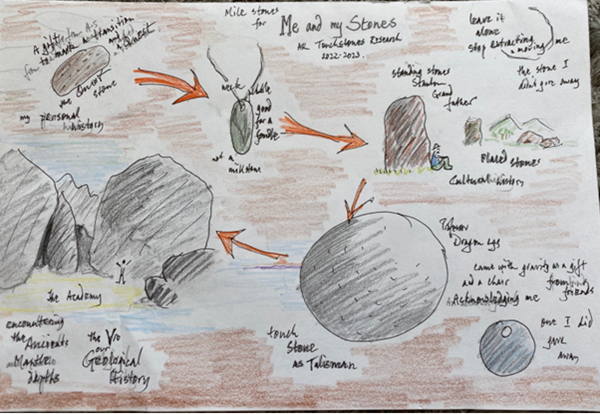

Written during and after my first Touchstone workshop. ‘Oolooks’ was the name the grandmother of a participant gave to attractive stones that her grandchildren brought her, some of which she displayed in a special glass jar in her home. Figure 1 below shows my favourite stones.

Touchstone – Moving from Palm to Planetary Crises and Back

In my pocket I finger a warm pebble, my touchstone. Be they worry beads, malas, or komboloi, many cultures and faiths have long used stones to ground us. Mine is dark, veined with red, a smooth piece of serpentine that once arose from 5 km below the Earth’s surface, the place where the crust meets the mantle below. I remember picking it up, glistening wet on the Lizard peninsula in Cornwall, a special place of sea caves and stacks. One result of my Touchstone research with my workshop participants is that I am surprised to learn just how many people have a special relationship with a chosen pebble, helping us cement contact with a memory of a loved one in a particular time and place.

I was born when there were 318 ppm of CO2 in the atmosphere, one third less than today’s 422 ppm and counting (Lindsey, 2024). The CO2 will persist for thousands of years, meaning the warming we have already caused since the industrial revolution is irreversible, even if emissions were stopped now, as is required (Matthews & Solomon, 2013). This is not happening because of a lack of political will, due to the capture of democratic process and civic discourse by Big Oil lobbyists (Brulle, Hall, Loy, & Schell-Smith, 2021; Lucas, 2021). Meanwhile, we are still fuelling the highest ever recorded global temperatures (WMO, 2024). Hence the Anthrobscene, a moral judgment on the climate crisis which points to the obscenity of the Anthropocene precisely because it is avoidable (Parikka, 2014). The Anthrobscene is my chosen alternative designation, although many others are available, such as the Capitalocence, the Necrocene, the Pyrocene and the Corporatocene.

Which brings us to one overriding question: How on earth do we hold the man-made crisis of the now? For me one small, perfectly weighted, and curiously reassuring answer is nestled in my palm—a smooth serpentine pebble that morphs through time and place. Is there something here that can speak to others too? I wanted to know. Touchstone has emerged in response to enquiring whether engagement with the deep time dimensions of rocks through creative writing can help equip us deal with the climate crisis. Data and feedback resulting from my Touchstone research confirms that it can and does.

Stone might seem elementally different to us, hard to our softness, slower to decompose, yet composed of it we most certainly are. Our bodies depend on earth-derived minerals such as calcium, iron, potassium, sodium, and magnesium. Touchstone asks, What happens when we encounter our stonier, elemental selves? During the current planetary polycrises, why is the element of earth as expressed by rocks and deep time receiving ever-increasing attention (Bjornerud, 2018, 2024; Cohen, 2015; Macfarlane, 2019; Allen, 2024; Jamie, 2024)? Some publishers are even referring to this as being the new Stone Age. What, if anything, changes in us when we tune into rock and try to think and feel through the medium of stone, questing its muteness? Is there indeed a lithic deep time wisdom that we can access?

The veined red stone in my palm is not any old pebble, it is a storied stone, a silent witness to inordinate change, a talisman that I hold close and confer with. The Touchstone project combines geological knowledge with proven regenerative approaches that can support us, harnessing the practices of creative writing for therapeutic purposes (CWTP). There are indeed benefits to bringing people outdoors to collaborate with others, writing into rock during troubling times.

Much-in-Little

It all began with a stone

during my Precambrian,

swallowed deep and settling,

dropping down and down again

to hammer flint, struck sparks

promising fire and fossils,

the tell-tale tang of cordite in the air.Peel back the skin, the place where

ribs are revealed, where the land

runs out, where stones, our bones and sea

surely meet for conversations

with substrate, the place where the land

runs out of rock, quarrying wonder,

tall tales and wide horizons from the edge.

(Smalley, 2023)

‘Much-in-little’ is the term the geologist Richard Fortey gives to the variety of rocks found in the British Isles (2010, p. 10). The poem was inspired by a re-reading of my introduction to my Cornerstones collection of BBC Radio 3 essays that I produced (Smalley, 2018, pp. 7–13). It comprises 20 essays by contemporary writers and poets, each one exploring a chosen rock type.

Stone as Home

Once one becomes attuned to the language of rocks, it is obvious that Earth is vibrantly alive – and speaking to us all the time. (Bjornerud, 2024)

As a result of my Touchstone research year, I recognise that I harbour a deep, abiding, slow burn passion for rock that I carry close. It goes way back into my bedrock past, which must in part have paved the way for my later Touchstone interests, as conveyed in my poem ‘Much-in-Little’ and the book of essays I edited, Cornerstones (Smalley, 2018) through my work as a BBC radio producer. For that BBC Radio 3 project, I commissioned 20 contemporary poets and writers to riff with rock, and it was a joy to make all of them, each one recorded on location, in proximity to the stone in question. Alan Garner’s essay on flint captures the arc of human civilisation in 2200 words.

Stones and rocks peopled my childhood as objects of sheer wonder, containing the promise of fire, ocean beds, devils’ toenails, and dinosaur eggs. Such improbable creatures extracted from the clay pits behind my Northamptonshire primary school, a forbidden zone, beckoned from the shelves in the old Victorian assembly room.

Metaphor is a rich resource to draw on when engaging in creative writing, but for me, geological fact alone can evoke a rewarding space for imagination and creativity to populate, like slow crystals in a geode. Stone talks to me, with all the paradox that its mute silence implies. But how can stone convey anything other than stubborn obduracy? The Touchstone project has confirmed that I am not alone in my affinity with the world of rock. For me, and indeed as I have seen for my workshop participants, this sense of kinship can offer an important tool in the face of the Anthrobscene. The quality of stone’s vitalism, drawing on Abrams, Harding, Ghosh, Reason, Allen and others, opens up a sense of reverence for the multispecies, more-than-human world, which includes the mineral life of rocks. The testimony of my workshop participants affirms the robustness of Touchstone’s underpinnings, confirming its therapeutic, regenerative qualities as a new and viable expression of CWTP.

Since completing the year-long study for my CWTP MSc with Metanoia Institute in autumn 2023, I have developed my practice. I have gone on to offer Touchstone workshops in different settings, honing the offering with a class of 8-year-olds, a writing group composed of experienced secondary school English teachers, 40 festival goers at Buddhafield, and 35 creative writing practitioners, members of the Lapidus Living Research Community. I am also using Touchstone reflective writing techniques while co-running Deep Time Walks with geology educator, Mathilde Braddock. Such walks, developed by the late Stephan Harding of Schumacher College, shrink 4.6 billion years of Earth’s unfolding story into a 4.6-km walk, when each metre represents one million years. They offer an embodied way of clocking our relationship with deep time and the Earth beneath our feet. Including the opportunity for reflective writing on the walks helps participants incorporate the vast scales of deep geological time underfoot.

Time and the Crisis of Now

Grasping deep time is bewildering: it has perplexed people since the emerging science of geology unseated the biblical myth of the Earth’s creation within a single week (Lyle, 2016, pp. 40–45). Yet given the scale of today’s climate and nature polycrises, time is clearly of the essence. Why then do corporations and governments continue with business as usual, as if we have all the time in the world? Contradictory responses to the urgency of our Anthrobscene times are nothing new in human culture: such dichotomies might instead be simultaneously held and understood rather than rejecting one in favour of another (Gould, 1988, pp. 191–200).

Time itself is paradoxical, quicksilver slipping through our fingers. It can be understood as a unilinear, Newtonian arrow, and/or indeed as being cyclical, its recurrent patterns revealing deep natural structures (Gould, 1988, pp. 199–200). The future geological record may well point back to the Anthrobscene as marking the Sixth Extinction, indicated by the pervasive presence of nuclear fallout, microplastics, and chicken bones. Unlike the meteor strike that abruptly ended the dinosaurs’ Cretaceous–Paleogene era 66 million years ago, Anthrobscene changes are by definition of humanity’s making. The dinosaurs were blameless; neoliberal extractive capitalism is not.

Disavowal, Denial and Anxiety

The rate of current global heating is so rapid that it can be hard to grasp. That is not a reason for not trying. Climate scientists focus on an event some 56 million years ago when there was a rapid injection of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. It is called the Paleocene–Eocene thermal maximum, and it is studied because it is the most recent example of rapid global warming, which occurred over some 15,000–20,000 years. Scales and estimates vary, but some scientists suggest that the current rate of carbon release is ten times greater than then because it is happening over decades and centuries rather than millennia (Mann, 2023). Yet the UK parliament that declared a climate emergency in 2019 was contradicted by a government that reneged on its net zero commitments while licensing new oil, coal, and gas extraction. This is the living, breathing definition of disavowal, seeing the climate and nature crisis but ‘with one eye only’ (Weintrobe, 2012, 2021, pp. 137–138).

We negate or minimise reality at enormous cost to ourselves and the more-than-human world, cocooned from it by our white-knuckled sense of exceptionalism (Weintrobe, 2012, p. 15, 2021). It is not surprising that living in this current moment, straddling its screeching dissonances, causes me considerable and permanent stress. For me as a BBC radio producer, I also experienced moral distress. That is because it was not until 2019 that BBC News dropped its requirement that when covering climate stories scientists were ‘balanced’ with deniers. I am reassured that my symptoms of eco-anxiety represent a very reasonable physiological and emotional response to the situation we are in (Hickman et al., 2021).

It is an understandable response to turn away from our escalating climate crises and bury our heads in the sand. By contrast, however, Touchstone encourages us to acknowledge these considerable psychic forces while digging deep into the earth and our imaginations for a different purpose. Not to seek denial or distraction, but to quarry uncomfortable truths ‘in tension and fruitful interaction’ (Gould, 1988, p. 200) while using CWTP techniques to engage our imaginations with compassion, curiosity, and insight.

Why Deep Time’s Time Has Come

When viewed in deep time, things come alive that seemed inert. New responsibilities declare themselves. A conviviality of being leaps to mind and eye. The world becomes eerily various and vibrant again. Ice breathes. Rock has tides. Mountains ebb and flow. Stone pulses. We live on a restless Earth (Macfarlane, 2019).

The most productive pointers for the Touchstone project have emerged from strains of deep ecological writing (Macy & Johnstone, 2022; Reason, 2023), aspects of Gaia theory (Lovelock, 2006; Harding, 2009) together with the flourishing discipline of the environmental humanities (Haraway, 2016, Harris, 2021), and, curiously, medieval studies (Cohen, 2015; Power, 2022). Deep ecology faces several ways at once—back towards a pre-Cartesian world in which the Earth itself was recognised to have sentience or a vital spirit and forwards to an understanding that humanity is only one of many equal components represented by Gaia’s global ecosystem. Some of these approaches (Reason, 2023; Harding, 2009; Allen, 2024) share an engagement with the material world of stone, challenging presumptions that rock is merely a blank, inert substrate. This aligns with the recognition of one’s ‘ecological self’ (Naess, 1987), the part of us that exists within a wider natural world in which all species and the more-than-human world can flourish. It follows that a wider sense of ecological responsibility beyond one’s narrow self-interest can flow when we allow for conventional selfhood to extend beyond the ego. This is what the Touchstone project is rooted in.

A necessary and long overdue paradigmatic shift is well under way, which has knock-on effects way beyond the earth and life sciences. Gaia and deep ecological approaches have encouraged thinkers in other disciplines to see the elemental earth, particularly its rocks and waters, as vibrant (Ghosh, 2022; Haraway, 2016; Allen, 2024; Harding, 2009; Reason, 2023). Ancient Chinese culture recognises this life force as chi, the energy that links animal, vegetable and mineral states (Armstrong, 2022, p. 32). Earth-focused therapeutic approaches (Richardson, 2023; Allen, 2024) inform the Touchstone approach, which I combine with Macy’s regenerative concept of active hope and CWTP’s practices that enable a reflective space where play, observation, creativity, and wonder are actively encouraged in service of Gaia (Ghosh, 2016).

Stone has conventionally marked what can appear to be a firm, intractable boundary between ‘humanity’ and ‘nonhumanity’. But the haecceity, the it-ness of rock, is rather more fluid than the old Victorian parlour game of ‘animal, vegetable, mineral’ might once have once presumed (Cohen, 2012). Medieval Christian theology allowed for a world view in which rocks were permitted mineral souls with almost lifelike attributes. Sometimes they were allegorically endowed with human emotions and drives (Cohen, 2012, pp. 92–93). Some current deep ecological thinking promotes a contemporary version of that medieval world view, arguing that ancient rocks possess a consciousness which has something resembling a consciousness deeper than ours (Harding, 2009).

Welcome to the world in which ‘rocks are not nouns but verbs—visible evidence of processes’ (Bjornerud, 2018, p. 8), distinctly active, and rather more than just present tense. Rock is an emblematic remembrancer of deep times past which, in the face of the Anthrobscene, confounds our sense of time in the present.

The wider project that Touchstone allies with is considerable, to resource ourselves in order to stand with all life for a different, post-hydrocarbon way of being in the world, thus relating more healthily to nature, our environment, and the Global South. But in doing so we have to grasp a world in which, seen through a deep time lens, we ‘have hardly yet to exist,’ but also one in which humanity may not exist at all (Cohen, 2018, p. 23). The Touchstone challenge is to work fruitfully with perceptions of deep time and the recognition of our hapless insignificance to encourage us into action rather than apathy.

Nature, Rocks and Wellbeing

The Touchstone series of workshops are underpinned by a set of established evidence-based principles that confirm the significant health benefits that derive from people spending time together outdoors in nature, evidence that supports, for example, the rapidly developing field of green social prescribing (Richardson, 2023), the rollout of which is supported by the UK National Health Service (NHS). At the time of writing (summer 2024) the University of Exeter’s Nature on Prescription Handbook along with ongoing research undertaken by the University of Derby’s Nature Connectedness Research Group (Richardson & Butler, 2022) represent the best practices available in UK today, laying out the proven benefits of people reconnecting with nature outdoors.

Of particular relevance to my Touchstone research, the intersection of engaging with the arts in nature in the company of others is shown to have a powerful effect on us, particularly when the five pathways to nature connection are engaged (Richardson & Butler, 2022, pp. 10–13). These pathways identify the benefits of being in nature when all our senses are involved, beauty is observed, our emotions are engaged, meaning is found, and our compassion is frequently evoked. I grounded my Touchstone workshops in this growing body of evidence, in particular encouraging participants’ sensory experience of rock during the workshops.

CWTP in the Context of Nature and Wellbeing

The beautifully shaped stone, washed up by the sea, is a symbol of continuity, a silent image of our desire for survival, peace and security. —Barbara Hepworth

Accompanying the growing evidence-base supporting how spending time in nature improves our wellbeing, there is also increasing interest in the arts’ contribution to health, one tributary of which focuses on writing for wellbeing. The act of writing produces beneficial effects when we express thoughts on the page, it helps us understand the world around us, promoting self-understanding (Pennebaker, 1990, pp. 91–93). CWTP’s emphasis on play, experiment, and discovery is important for Touchstone, given the enormity of the issues at stake, encouraging one’s Natural Child to engage in the writing with a focus on the here and now (Williamson, 2014, p. 10). Given the chance of upset and overwhelm when engaging in a creative and emotional way with the climate and nature crises while writing into rock, it is all the more important that participants feel they are in a safe enough, well-held workshop setting.

CWTP can help us process trauma by translating emotional experiences into language (Pennebaker, 1990, p. 101). Touchstone harnesses these techniques to support participants to address the overwhelming existential trauma of the climate crisis, but safely sidelong, not head on. Participants are invited to converse with rock, as it were, to give it voice, and to see what emerges during the exchange. As the poet Emily Dickinson puts it: ‘Tell all the truth, but tell it slant./ Success in circuit lies.’

Joanna Macy’s Work That Reconnects

My Touchstone workshop design was richly informed by Joanna Macy’s empowerment strategy for environmental activists known as the work that reconnects (TWTR). She and colleagues have been developing it since 1978, and it is most recently laid out in her book, Active Hope: How to Face the Mess We’re in with Unexpected Resilience and Creative Power (Macy & Johnson, 2022). The technique draws on many life-sustaining traditions—including deep time and deep ecology—which encourage activist groups to resource themselves with solidarity and courage. Active hope can be understood as setting a muscular intention in support of the abundance of life on Earth.

TWTR offers a four-step spiral process (Macy & Johnson, 2022) that amounts to inner resourcing for outer action. The active hope cycle (Figure 7)

- invokes gratitude;

- acknowledges the grief and other powerful feelings we can hold regarding our experiences of the planetary crisis. By means of honouring these feelings the spiral enables participants to then

- ‘see anew with ancient eyes’ (which includes a deep time dimension) before

- ‘going forth’.

The intention of Macy’s work is to enable activists to mitigate the risk of burnout and overwhelm in order to undertake outer action in the world. The cyclical nature of TWTR—similar in that sense to the action research model of planning, doing and reviewing that I used—profoundly informs Extinction Rebellion’s concept of Regen, a model of wellbeing that encourages self-care (Extinction Rebellion, 2019). Feedback from Touchstone participants confirms that they found their involvement in the process to have been rewarding, enabling them to go forth with renewed vigour, affirming and completing the cycle of Macy’s TWTR.

Touchstone Workshop Structure and Content

I have learned that plenty of time outdoors is required to engage with rock and then to write and share about the encounter, because for many this is a new and unfamiliar but rewarding activity. Appendix 1 offers a model Touchstone CWTP workshop, with information and resources compiled from the different prompts and techniques that I offered the seven participants across my series of three research workshops. I will briefly sketch them out here.

After an initial online Zoom-based gathering to lay out the project’s ground rules, the seven participants and I met at Clevedon foreshore on the North Somerset coast for a three-hour workshop. It was March and cold, so I provided a lunch of soup beforehand, which was appreciated. I was accompanied by one of my two co-researchers who were on hand to help out if necessary. Otherwise, they were acting as observers.

I invited people to recall happy times in the past which they might have spent on beaches discovering pebbles and rock pools. With Macy’s TWTR in mind, this was a way of invoking gratitude for our being together on the North Somerset foreshore. People were then encouraged to find a rock and to sensorily engage with it, whether to look at it or lie on it, without doing anything else. Then to note what came up, and to write out of those observations. Passers-by were intrigued. We then came back together when participants were invited to share their insights and their work if they wanted to.

I went on to explain that rising sea levels threaten the coastline, which is likely to look very different in 50 years’ time, given the likely reclamation of the nearby Somerset Levels by the sea. This was to invoke the second step on Macy’s TWTR spiral, honouring the pain we feel for the world.

In terms of offering writing prompts and a means of engaging with rock itself, I have learnt that Charles Simic’s poem ‘Stone’ offers a remarkably useful window that opens onto core Touchstone territory. Inviting wonder, imagination, and conjecture about the vitalist nature of stone, I cannot recommend it enough. I was so impressed with what a class of 8-year-olds came up with in response to it during a Touchstone workshop with them. Likewise, offering prompts from works by the doyen of rock poetry, Alyson Hallett (2019, 2020), is enormously fruitful.

Inviting participants to spend time lying on the foreshore rocks before writing about it offers an opportunity to ‘see anew with ancient eyes’, the third aspect of Macy’s TWTR. Doing so can enable us to see ourselves as part of a larger whole, moving beyond any narrow sense of the here and now. It is a way of entering not only geological deep time but also achieving an affinity with rock, an almost cross-species practice of ‘becoming with one another’ (Donna Haraway, 2016, p. 80). People’s responses, writing, and feedback all confirmed that these steps were helpful. Other useful prompts included inviting participants to dialogue with their chosen rock by asking it some who? what? when? where? why? questions and noting what came back.

Anticipating people’s potential resistance to writing creatively together, I had shared in advance my tutor Nigel Gibbons’ helpful acrostic ‘Writing Well’ (2012). It proposes a way of approaching CWTP by acknowledging and working with one’s inner critic. In addition, the one-liner prompts and quotes about rocks in Appendix 2 stimulated much thought and discussion, particularly when giving people the opportunity to respond to them with some short warm-up writing exercises, which is how we began the third workshop.

A weakness of the study is that I only offered the three workshops. This was because I was working not just on my own material and observations in an autoethnography but including those of my two co-researchers and seven workshop participants. This produced a wealth of data for me to assess, which I had to restrict to keep the whole thing manageable. I struggled to marshal all this input, feeling a weight of responsibility to include their voices as co-participants alongside mine. Now that I am beyond the research phase, I can see clear benefits for participants in offering a longer series of Touchstone workshops. This would enable people new to CWTP techniques to gain greater familiarity and confidence with, for example, undertaking short writes in dialogue with rocks in outdoor locations and sharing the results.

Action Research Methodology

As a methodology, the cyclical iterative process of action research (AR) enabled me to develop the Touchstone technique through framing a research question, trialling it during a writing/research session and then evaluating the participatory work that emerged in response to it. Furthermore, AR has enabled me to phrase open, permissive questions such as

- I wonder what would happen if... we spend time focusing on our relationships with the Earth via rocks.... and

- How do I...? / How do we... find ways of sharing our experiences?

Such questions enabled me to use AR as a practice-based form of research while developing my provisional ideas first with my co researchers and then, having honed them, with my workshop participants.

The collaborative inquiry aspect of AR (Reason & Bradbury, 2001, 2008) offered me and my two co-researchers, Alan and Paul, a democratic means of recognising our joint and equal participation, primarily because the approach advocates working with others, not on them. This sense of being peer led was already familiar to us because it is how we have long related to each other in the men’s group that we are part of. It has been helpful that Alan has experience of AR, having studied it with Peter Reason, a leading exponent of the technique. Alan had tried to bring it into his work as an NHS consultant psychiatrist, which must have been no small undertaking. Together the three of us negotiated the simultaneous roles of being co-researchers and subjects, testing Reason’s proposal that researcher and subject are not separate, because these functions can coexist in the same person. For example, in terms of being collaborative and peer led, it was not always me setting the theme of our monthly outdoor Touchstone creative writing sessions.

Ethics

My Touchstone workshops were designed and run on the basis of respecting the confidentiality of participants, a key ingredient in the trusting relationship that counselling is intended to foster (Metanoia, 2015). I offered the workshops as a resource for activists who agreed to offer me feedback and share their creative writing. Their quotes are not attributed to individuals. Participants gave their permission for photos to be taken at the foreshore creative writing workshops and for them to be included in this paper. My co-researchers have given their permission to be named.

Throughout the whole Touchstone process, I continued with my therapy as a form of self-care. It has provided a robust container for the strong feelings of overwhelm and confusion I can experience in the face of the climate and nature crises. It also helped me address habitual feelings of self-sabotage and procrastination that I can experience. The sense of open and shared inquiry with my co-researchers helped create a sense of jointly owned purpose and accountability. However, meeting the academic criteria and writing up was my responsibility, though I felt supported and upheld by my co-researchers.

Given the climate focus of the workshops and anticipating the difficult feelings some participants might feel, I invited them to keep themselves emotionally safe. I also explained that I and one of my co-researchers were on hand should someone become upset. I was confident in my co-researchers’ ability to help in this way because they both have mental health backgrounds. This required proper consideration in advance, not least because Joanna Macy’s spiral, which I was following as an underpinning methodology, expressly offers an opportunity to feel and share one’s pain for the world. Metanoia’s Ethics Committee rightly asked me to confirm that my co-researchers would respect the confidentiality of the group, which they both agreed to.

Given that two of the workshops were held outdoors in early spring down on the foreshore of the Bristol Channel, the ethics process helped me risk assess my responsibilities to the participants, e. g.:

- What I would do if it was raining or too windy.

- Making sure I knew what time high tide was on the days I was running the workshops.

- Because of holding the workshops at a cold time of year on windswept foreshores, I decided to provide soup, drinks, and flapjacks for participants, which was welcomed.

Working with My Co-Researchers

Take a stone in your hand and close your fist around it—until it starts to beat, live, speak and move. —Sámi poet Nils-Aslak Valkeapää

I invited two old friends from my longstanding men’s group, Alan Kellas and Paul Welcomme, to join me on my Touchstone journey as co-researchers. We have a longstanding history of working together outdoors in nature, marking the seasons and life’s turning points, using ritual, close observation, and sharing. Why not throw in some creative writing too?, I thought. We met for one afternoon per month over a year-long period from May 2022 at rocky sites in the West of England, devising a varied cycle of Touchstone writing activities which informed my series of three workshops. We came to call ourselves the Palchemical Poets because of a Tom Gauld cartoon in New Scientist (2023) in which the depicted alchemists recognise that ‘the real gold was the friendships made along the way.’ That’s been our experience, that our friendships have deepened as a result of giving our focused attention to rock and stone, and sharing our writings about our experiences.

We learned that Clevedon foreshore is a geologically fascinating location. The ground under the pier is jewelled with rare semi-precious stones and minerals which resulted from past volcanic activity. It was also on Clevedon foreshore where my co-researcher Paul led us in a grief exercise. He invited us to find a stone to represent a particular grief. Thus named, the grief and the stone could then be laid down before one moved onto the next one. From my own writing during that exercise emerged a poem about my grandfather who survived his time in Flanders during the First World War.

Over the course of the year collaborating together, the three of us worked towards a visit to Stanton Drew’s stone circle in North Somerset. A place of ancient, intentionally placed stones, it is second only in size to Avebury in Wiltshire. We chose to delay the visit because between us we realised that there was so much to go at in terms of working with naturally occurring raw bedrock and pebbles, that engaging with worked rock imbued with social and quite possibly religious significance felt like a step change that needed careful preparation.

The Grief Stones

Low tide reveals drifts of buttery cream pebbles

bookended by low rocky ribs

which point skywards towards their past trajectories.This stone is for you, Grandpa,

William Ralph Cox, a good man undone by war.

For you, I select the one clean stone

found in a slippery trench of seaweed,

as suits the Flanders you say you survived.I lay you down, old man.

I release you, with oak leaves,

while releasing myself

from the obligationsyou laid on me.

No more bayonetting Germans

a full 50 years after you’re gone.

Stand down, Private, your duty is done.In laying down this stone I free myself

of the shadow of your war, though

written full well entrenched

in the climate crises.My regrets people this shore,

a graveyard waiting to be washed clean

by the next tide and the next,

resolved perhaps one grain at a time.

(Smalley, 2023, p. 114).

This poem was written during an exercise examining our regrets with co-researchers Paul and Alan on Clevedon foreshore. It’s been edited to a point where I feel comfortable to share it.

Findings Resulting from My Workshops and Participants

This is the first time I have ever seen geology as a living source of comfort and perspective. Rocks have started to come out of the landscape for me in a new way which I find both energising and peaceful. (Touchstone workshop participant)

I am reassured that this respondent found unexpected value in the workshops, confirming that they found their encounter with rocks to have been therapeutic. Another expressed surprise that they had ‘the ability to commune with a pebble.’

Writing into stone has been a useful way to engage with the element of Earth....I think that I have something to say/write/maybe even paint that makes sense of my experience as an ex-mineral’s planner and continuing climate activist. [Touchstone] has shifted me to include the ecological crisis more firmly in my climate activism. (Touchstone participant)

This feedback suggests a strong link between the creative activity of writing outdoors alongside others engaging with the climate crisis in the context of deep time as an inner activity, while also feeling resourced for outer action in the world. They go on:

The thin green life-layer, the vulnerable brown living soil layer, crushed and killed by privileged, mobile, sentient, conscious humans who are temporary custodians of a batch of ‘mineral molecules’ that came to us from the stars and will settle into geological layers eventually... This has given me a clearer passion and potentially a clearer voice. (Feedback from Touchstone participant)

Feedback such as above indicates a thoughtful engagement with many aspects of what I was trying to enable during the Touchstone workshops. The participant describes feeling a sense of renewal and being re-energised. Through the workshops this person potentially found ‘a clearer voice’ as an activist, corroborating my use of Macy’s TWTR approach. Significantly, the person’s engagement with deep time through reflecting on the nature of rock and its movement through time and space as elemental matter also implies a shift in their temporal perspective. Perhaps it is this component that better enables them to access a renewed sense of agency in the face of the present Anthrobscene polycrises. That for me counts as success.

Participants were grateful for the way I hosted this novel opportunity for activists to work together in unexpected ways and in such settings.

Just lots of thanks Mark. This was good because you brought yourself, with all that life, energy and intelligence, into the space. (Touchstone participant.)

Personal Findings

Shaping and delivering the Touchstone project across a whole year proved to be a novel, uncharacteristically structured (for me), ultimately rewarding opportunity. That said, it was also a frequently emotionally difficult learning experience. It was a mighty long time since I had done any studying, and the social science academic framing of CWTP was new and unfamiliar to me. There was the challenge of working out how much time and attention to devote to the research, moving through my own frequent heavy stuckness and procrastination—something I habitually struggle with —so that to have pulled these words out of my innards at all feels like no small achievement. Then there is the subject matter, the content: the heart of the Touchstone project addresses my deepest concerns about the Earth that I love like nothing else, and the bewildering dissonance I feel about what we, humanity, are doing to it. Knowingly exterminating other species while damaging ourselves (but pretending otherwise) is beyond words, beyond folly. For me it is truly maddening heartbreak.

I both welcomed and struggled with aspects of my chosen Action Research methodology. I felt tied in knots sometimes trying to accommodate not just my own views and insights, but also those of my co-researchers and workshop participants. I felt responsible for the enormous amount of data this level of collaboration produced, wanting to weigh and represent everyone’s contributions fairly. Would an autoethnography have been easier? Possibly, but the point is that with hindsight I can see that I have trialled my ideas with a wide range of people and continue to do so, enabling an active and ongoing refinement of the Touchstone offering.

Reflections on My Own Creative Writing

The creative writing I have produced alongside the research acts as a diary or record for me. I have learnt that my creativity is best enabled and expressed in collaboration with others. Nearly all the Touchstone poems I have written were either at my invaluable weekly Tuesday CWTP peer group Zoom meeting (meaning I at least wrote one poem per week) or indeed during the monthly Touchstone gatherings with my co-researchers, Paul and Alan, the Palchemical Poets. Altogether, this amounts to a substantial body of work that I have amassed, about 40 poems of my own work with a rock-based focus, the best of which I am preparing as a pamphlet. The whole creative journey has been a game-changer for me for reasons that I explore below.

Stone Stuckness

My stuckness is personal and particular to me, but it is something that may well resonate with that of others. I experience it as a heavy mass in my gut, indissoluble like a stone, rooted in inertia, with a low, grounded centre of gravity. Rather like a midstream granite boulder, my life and other emotions have long had to flow around this stuckness. It might be depression or overwhelm that I am describing. I finger this legacy of trauma tenderly, like a ripe bruise. During my Touchstone year I was invited to explore this visceral sense of stuckness by my co-researchers during several powerful writing sessions. This resulted in poems that have a particular meaning for me, e. g., ‘Geode Home’ which arose out of a ritual in my own garden. I trusted Alan and Paul’s urging me to undertake my own embodied Touchstone work rather than just offering exercises for them and my workshop participants. What resulted were grief-filled movement-based rituals to explore my stuckness, which some of my poems try to explore. Some of the poems are edited to a point where I feel safe enough to share them. But nonetheless the process of being held gently to account by my co-researchers was a growth area.

‘Geode Home’ resulted from me making a spiral labyrinth of my storied stones in my garden, treading my silent way to the hollow geode at the centre, approaching my stuckness. Witnessed by my co-researchers, it was a rich and revelatory experience. I am proud that my son Ben has illustrated the poem. Indeed, I recognise that a proportion of my poems explore aspects of imprisonment and release, combining qualities of considerable pressure, awe, insight, and privation. These, I realise, are some of my perennial personal themes which my fascination with rocks helps me explore and then articulate. Writing into these themes via rock has helped me find a sense of flow with this painful stuckness. That is not to say that it has been overcome, but through the Touchstone process I have learnt that I can sometimes dance with it, ponderously. This confirms one of CWTP’s acknowledged goals, acting as a tool of insight and self-discovery with an emphasis on play while connecting with one’s own creativity (Williamson, 2014, p. 9).

Touchstone and My Activism

Engaging in Touchstone during my MSc research year not only helped me engage more creatively in my activism, but my activism, I realise with hindsight, also helped me extend my creative endeavours. I am sure this in part expresses the self-reflexive nature of the Touchstone research process (Etherington, 2004). Attempting to name and own my own experience in relation to the contributions of my co-researchers and my workshop participants did not come naturally because I was schooled in more conventional, less transparent methodologies. Nonetheless, by combining Macy’s TWTR with AR’s emphasis on working openly and collaboratively with others, I am proud that, besides developing my Touchstone work, that I have also co-founded a new, independent body called Climate News Tracker. This is an independent body that uses media monitoring technology to encourage improved reporting of the climate and nature emergency on the part of the UK’s public service broadcasters. This constructive process helps me deal with some of the fury and moral distress I carry regarding the failure of my former employer, the BBC, to better inform us, the public, about the truly galloping dimensions of the Anthropocene polycrises unfolding before our eyes. Bringing together creative writing and my passion for rocks on the one hand, and my concerns about the climate and nature crisis on the other, has felt like a fruitful interplay, as if bridging the different hemispheres of my brain. One result is that I feel more grounded and empowered and a little less stuck and self-critical, as if laying down new and unfamiliar neural pathways.

I recognise that there was considerable creativity in my work as a BBC radio producer, but I felt stymied by structural and management pressures which narrowly patrolled the margins of the sayable and the unsayable. I felt considerable conflict and moral distress around the Corporation’s heavily policed notions of ‘impartiality’ and ‘balance’ that governed the coverage of Brexit and climate issues. I was subject to these editorial pressures on a daily basis, and that was a heavy load of dissonance for anyone to carry. My experience is that this results in self-censorship. We as listeners and viewers are ill-served and misled by these codes. We deserve better. Bringing together my activism, my creativity, and my fury is bearing fruit, but it has not been an easy path to walk.

Leaving the BBC in 2018 proved to be a release for me. Engaging in Touchstone and my ongoing journey through CWTP has helped me find a way beyond my radio career, one that permits me a voice that felt forbidden whilst a member of staff. I am grateful for this unfolding process of recovery, decompression, and self-reclamation. I have experienced the satisfaction of sharing my insights with others, for example in workshop settings, whilst also enabling people to engage with their own creativity. In some cases, participants were returning to creative writing for the first time in decades. Facilitating that feels like a mighty privilege.

Stones and Feeling States

The Touchstone process has helped me recognise that I find it deeply satisfying to physically connect and ‘think with stone.’ Stone has evidently been abidingly good for humans and pre-hominids to think-feel-do with for time out of mind. Archaeologists have evidenced the development of the earliest hominids through their shaping of stone, whether as tool, decorative artefact or memorial, a symbolic remembrancer that long outlives a single lifetime (Cohen, 2015, p. 23).

It is not just a case of speaking or thinking about the material qualities of heft, weight, and texture of stone (which I of course find attractive) but about the symbolic meanings, associations, and feeling states that they offer, too. This has been the case throughout human cultures, resulting in a paradox deftly captured by the poet Kenneth Koch in ‘Aesthetics of Stone’:

The gods take stone

And turn it into men and women;

Men and women take gods

And turn them into stone.

(Koch, 1994)

I am fascinated that stone operates simultaneously as both metaphor and metonym, at one and the same time fulfilling a wide range of functions. The Touchstone project offers pebbles as both self-soothing transitional object and synecdoche, linking the part to the whole. The red-flecked serpentine pebble in my pocket links me with the Earth and grounds me. I am reassured to discover that this is the case for others too—talking to the planet with a pebble.

My Findings with My Co-Researchers

I am struck that my two co-researchers took Touchstone in their own very different directions. Alan developed a meditative practice in relation to his touchstones, while Paul used it as a means of reckoning his mortality, ‘exploring pebbles to pay the ferryman whilst navigating the steppingstones to the River Styx’ as he puts it. Alan writes:

What I have particularly valued is sharing my curiosity about the emergence of inner truths, not yet the fully formed version… we have explored widely the link between the solidity of earth, stone and rock, and the apparent (if relative) permanence of geological processes compared to psychological processes... I remember too and now appreciate more deeply the bones in my body, which come from and will soon return to the mineral earthy reality that is our place on ancient common ground. (Smalley, 2023, p.136)

The patience and investment of my co-researchers in this project has helped it grow as it became important to each of us in our respective ways.

We concluded our participative enquiry in May 2023 by spending five days together on the Lizard in Cornwall (the source of my treasured serpentine touchstone). Among varied writing and stone-based activities on cliffs and in coves, we carved our own pieces of serpentine with a sculptor, Don Taylor (Figure 15). Smoothing and shaping it by hand felt like a fitting culmination to our lithic journey together. It was a deeply satisfying experience to polish stone, joining hand, heart, and eye. It is an activity that I still delight in.

Together the three of us co-researchers very much developed an ongoing practice around writing into stone. We have since spent a year flowing with the element of water and are about to engage with the element of air and then fire. We are changed as a result, and our friendships have deepened because of the ways we have helped each other along the elemental Touchstone camino.

Discussion

There will always be change, there will also be continuity—the secular is sacred, and the ephemeral is eternal. (Bjornerud, 2024)

Engaging playfully with the lithic world combining CWTP with deep time activities enables a recognition that other worlds and other ways of being are possible. I believe this confirms that a gentle radicalism lies at the heart of CWTP as being something that is fundamentally regenerative. It can stimulate our active hope and imagination in ways that are beneficial for us (Williamson, 2014, p. 10). The deep time evidence written in the rocks confirms that other worlds have existed long before us. Change is a given, and our present moment will sure enough soon be replaced by other worlds still to come, whether or not it is witnessed by humans.

For myself, I have experienced working with and being upheld by my co-researchers and on occasion being rightly brought back to task by them. I could not and would not have achieved this on my own. The result is broader and richer than were it composed of my words and insights alone. This is a strength of the open, collaborative Action Research methodology I used, and it is evidenced by the insights of workshop participants.

Lithic journeys are so much longer and slower than ours, but they are journeys nonetheless (Bjornerud, 2024, p. 8). In a sense, when engaging with rock we are touching not just the infinite and the infinitely variable, but also a testament to our own mortality. I take the feedback from Touchstone participants to confirm that there is a self-protective dimension to looking slantwise at the climate crisis through deep time as enshrined in rock. The safely held setting of the workshops and seeing our brief lives in the light of deep time offers a foil by which we can approach this Anthrobscene moment. Writing into this bewildering territory with a degree of lightness and playful inquiry is recognised by CWTP practitioners as having a healing function (Bolton, Field, & Thompson, 2006, pp. 124–128).

The creative writing component of Touchstone enables us to give form to our thoughts, fears, and observations by getting them down on the page, where we can look at them as something external to us (Pennebaker, 1990, p. 91). It is something that can then be moved around, altered, played with. There is—to use a geological analogy—a metamorphic power to writing poetry: doing so is transformative.

Conclusion

Be humble, for you are made of dung, Be noble, for you are made of stars. (Serbian saying)

By means of conducting my Touchstone research I have learnt that, modest though its contribution may be, the use of CWTP in the context of the climate and nature crises offers an imaginative, regenerative space in which we can feel supported to think–feel our ways towards dealing with the shocking crisis of the now. It is no small thing to render the Anthrobscene somehow workable because it is the most intransigent outer circumstance that I can think of. Yet this, I believe, is what has occurred for me, my co-researchers and participants during the Touchstone process. The softening of grief and overwhelm is achieved in part, I suggest, because focusing on rocks and writing about the encounter with curiosity, sometimes accessing wonder and awe, enables us to safely deepen our experience of our ecological selves (Naess, 1987).

As the climate and nature crisis deepens and unfolds, so too must our engagement with the more-than-human aspects of our humanity (Ghosh, 2016; Haraway, 2016). It takes enormous strength to step beyond society’s powerful structures that enforce the widespread disavowal of what is unfolding in real time before us, but nonetheless Touchstone offers one modest means. The possibility of other futures besides neoliberalism’s ‘business as usual’ growth mantra can be entertained when we permit ourselves creative, regenerative playtime as offered by CWTP in a safely held Touchstone context. Recognising our kinship with the more-than-human world, which includes the vitality of rocks, appears to have touched all the study’s participants.

Touchstone can be adopted as a practice, like a meditation, as my co-researcher Alan has shown, routinely checking in with the earth’s hard parts that exist within us. Crucially, other, more circular ways of experiencing time can be invited to come into play in our lives, hence in part my co-researcher Paul felt enabled to lean into and own his mortality whilst accompanying each other on our Touchstone journey together.

Carving out time for ourselves to conjure and imagine is a gently radical, regenerative act. By these means the Touchstone process allows for the creative imagining of a just transition to zero carbon societies, recognising, for example, the need for climate justice for all, particularly for the inhabitants of the Global South, who are already bearing the brunt of global heating. It is increasingly being felt across Europe too.

Touchstone invokes a geology that encourages grounded, earth-based wonder, close observation and appreciation of our time and place, witnessing this Anthrobscene moment of a self-inflicted boiling, burning earth. Touchstone invites us to draw upon an intentional sense of active hope, resourcing ourselves by going to an elemental rocky place, lying back on the rocks, feeling the Earth beneath our bodies, and writing creatively from that place. Being curious about rock and stone while feeling into its dense obduracy offers us a means of healing the softest, most wounded parts of ourselves and therefore the Earth itself.

I finish writing this paper at the Monteneuf menhirs in southern Brittany. Less well known than Carnac, their abiding presence was only revealed by a forest fire in 1976. Vast fallen monoliths of schist were revealed, having been intentionally brought here, fashioned, and raised some 6500 years ago.

I do what I have invited my workshop participants to do, and connect sensorily, sensually with the rock. I take my shoes and socks off and lie on a long-fallen stone, two and a half times longer than I am tall. I stop and breathe deeply, feeling supported by it. A charm of finches flits overhead. The oak leaves stir in the wind below a blue sky. A woodpecker is tapping. I’m hungry, it’s lunchtime.

It is well worth asking the big questions in these places: 260 generations have come and gone since these stones were erected. What might a community’s intention have been in positioning them here so long ago, a special site that was in active use for some 1500 years, tended to by 60 generations? Also, and no less unanswerable, what will these lands and our descendants be like in 6, 60, or 260 generations hence? In terms of our own brief stewardship of this matrimony, what will the consequences of our own brief hydrocarbon-fuelled contribution have been?

The questions posed in Mary Oliver’s poem ‘The Summer Day’ (1992) come to mind: ‘Doesn’t everything die at last, and too soon? Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?’

For me the struggle and the allure of human deep time is placing my own mortal fears in the context of ancestors long past, and indeed hopefully those who are still to come. Deep time pitches forwards as well as backwards. How on earth can we deal, Cassandra-like, with the knowledge that our blinkered avarice has so tipped the scales that entire species are being wiped out now during the Sixth Extinction, with the climate irrevocably changed by our behaviours?

Before me stands a 5-m tall rectangle of dark schist, utterly monumental, like the megalith in 2001 A Space Odyssey, I hear someone say. Like a person, it is broader front-on, a narrowing pinnacle from the side. Two small bright lichen discs look out from the top. What do they see? And if this rock could speak, rain streaks like tresses falling over its shoulders, what would it say?

I am haunted and consoled by the paradoxical wisdom of Goethe’s aphorism about rocks—that it is precisely their silence that makes them the greatest teachers.

In my pocket I finger my Touchstone, a rounded piece of red serpentine. It grounds me on this earth, my home.

Being Rock

After ‘Being Water’ by Tamzin Pinkerton

Being rock has bottom, grounded

ballast rounded in slow flowform downhill, finding

my level, our belonging in mystery, boulder fields

of conversant beings.Being rock is slow flowform,

to all time flings, is knowing all these flows

within, crystals reposing, recomposing,

is boulder meeting deep bedrock being.

(Smalley, 2023)

Acknowledgements

Thanks to my Research Advisor, Amy Rose, and to my tutors on the CWTP MSc at Metanoia. Thanks to my co-researchers Alan Kellas and Paul Welcomme; to the geologist and therapist Ruth Allen for sharing the typescript of her book, Weathering (2024). And thanks to the seven participants in my series of Touchstone workshops for their contributions, to my wife Sue for being a rock, and to our children, Ben and Ella, chips off the old block.

Mark Smalleyis a Bristol-based freelance radio producer who has used his MSc in CWTP to look at rocks, writing, deep time, and the climate and nature crises. For much of his career he was a BBC Radio 4 producer of features and documentaries, specialising in poetry, history, and landscape-based programmes. He is a co-founder of Climate News Tracker, which is encouraging improved journalism around the Anthropocene on the part of the UK public service broadcasters.

References

Allen, R. (2024). Weathering. Ebury/Penguin Random House.

Armstrong, K. (2022). Sacred nature: How we can recover our bond with the natural world. Bodley Head.

Bjornerud, M. (2018). Timefulness: How thinking like a geologist can help save the world. Princeton University Press.

Bjornerud, M. (2024). Turning to stone: Discovering the subtle wisdom of rocks. Flatiron Books.

Bolton G., Field, V., & Thompson, K. (Eds.). (2006). Writing works. Jessica Kingsley.

Brulle, R. J., Hall, G., Loy, L. & Schell-Smith, K. (2021) Obstructing action: Foundation funding and US climate change counter-movement organization. Climatic Change, 166(17). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-021-03117-w

Cohen, J. J. (Ed.). (2012). Animal, vegetable, mineral: Ethics and objects. Santa Barbara, Oliphaunt Books.

Cohen, J. J. (2015). Stone: An ecology of the inhuman. Minnesota University Press.

Etherington K. (2004). Becoming a reflexive researcher. Jessica Kingsley.

Extinction Rebellion. (2019). Regenerative action cycle. https://extinctionrebellion.uk/act-now/resources/wellbeing/

Fortey, R. (2010.) The hidden landscape: A journey into the geological past (2nd ed.). Bodley Head.

Gauld, T. (2023, February 15). Palchemists cartoon. New Scientist. https://www.newscientist.com/article/2359667-tom-gauld-on-the-palchemists/

Gibbons, N. (2012). Writing for wellbeing and health: Some personal reflections. Journal of Holistic Health, 2( 2), 8–11. https://bhma.org/wp-content/uploads/woocommerce_uploads/2017/06/JHH9.2_article02_.pdf

Ghosh, A. (2016.) The Great Derangement: Climate change and the unthinkable. University of Chicago Press.

Ghosh, A. (2021). The nutmeg’s curse: Parables for a planet in crisis. John Murray.

Gould, S. J. (1988). Time’s arrow, time’s cycle: Myth and metaphor in the discovery of geological time. Penguin.

Hallett, A. (2019). Stone talks. Triarchy Press.

Hallett, A. (2017). Tilted ground. The Stone Library.

Harding, S. (2009). Animate Earth: Science, intuition and Gaia. Green Books.

Haraway, D. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press.

Harris, P. A. (2021). Rocks. In J. Cohen & S. Foote (Eds.), The Cambridge companion to environmental humanities (pp. 199–213). Cambridge University Press.

Hickman, C., Marks, E., Pihkala, P., Clayton, S., Lewandowski, R. E., Mayall, E. E., et al. (2021). Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: A global survey. Lancet, 5(12), E863–E873. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(21)00278-3/fulltext

Jamie, K. (2024). Cairn. Sort of Books.

Koch, K. (1994). On aesthetics. One train (pp. 55–74). Knopf.

Lindsey, R. (2024). Climate change: Atmospheric carbon dioxide. Climate.gov. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/climate-change-atmospheric-carbon-dioxide

Lovelock, J. (2006). The revenge of Gaia: Why the Earth is fighting back – and how we can still save humanity. Allen Lane.

Lucas, A. (2021) Investigating networks of corporate influence on government decision-making: The case of Australia’s climate change and energy policies. Energy Research & Social Science, 81, 102271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102271

Lyle, P. (2016). The abyss of time: A study in geological time and earth history. Dunedin.

Macy, J., & Johnstone, C. (2022). Active hope: How to face the mess we’re in with unexpected resilience and creative power (revised). New World Library.

Macfarlane, R. (2019). Underland: A deep time journey. Hamish Hamilton

Mann, M. (2023). Our fragile moment: How lessons from the Earth’s past can help us survive the climate crisis. Scribe UK.

Matthews, H. D., & Solomon, S. (2013, April 26). Irreversible does not mean unavoidable. Science, 340(6131), 438–439. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1236372

Metanoia Institute. (2015). Code of research ethics and conduct. https://www.metanoia.ac.uk/media/1979/mrec-code-of-research-ethics-v2-2015-1.pdf

Naess, A. (1987). Self-realization: An ecological approach to being in the world. The Trumpeter: Journal of Ecosophy, 4(3), 35–42. https://trumpeter.athabascau.ca/index.php/trumpet/article/view/623

Oliver, M. (1992). The summer day. New and selected poems. Volume 1. Beacon Press.

Parikka, J. (2014). The Anthrobscene. University of Minnesota Press.

Pennebaker, J. (1990). Opening up. The healing power of expressing emotions. Guilford.

Power, A. (2022). The history and deep time of climate crisis. Worldviews: Global Religions, Culture and Ecology, 26(3), 196–215. https://brill.com/view/journals/wo/26/3/article-p196_3.xml

Reason, P. (2023). Learning how land speaks. https://peterreason.substack.com/

Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. (Eds.). (2001). The SAGE handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice. SAGE Publications.

Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. (Eds.). (2008). The SAGE handbook of action research (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781848607934

Richardson, M. (2023). Reconnection: Fixing our broken relationship with nature. Pelagic Publishing.

Richardson, M., & Butler, C. W. (2022). The nature connection handbook: a guide for increasing people’s connection with nature. Nature Connectedness Research Group, University of Derby. https://findingnatureblog.files.wordpress.com/2022/04/the-nature-connection-handbook.pdf

Smalley, M. (Ed.). (2018). Cornerstones: Subterranean writings. Little Toller.

Smalley, M. (2023). Touchstone [unpublished CWTP MSc dissertation, Metanoia Institute].

Weintrobe, S. (2012). Engaging with climate change: Psychoanalytic and interdisciplinary perspectives. Routledge.

Weintrobe, S. (2021). Psychological roots of the climate crisis: Neoliberal exceptionalism and the culture of uncare. Bloomsbury Academic.

Williamson, C. (2014). When TA met CWTP. The Transactional Analyst, 4(4) 9–12.

World Meteorological Organization (WMO). (2024, July 25). UN Secretary-General issues call to action on extreme heat [Press release]. https://wmo.int/news/media-centre/un-secretary-general-issues-call-action-extreme-heat-0

Appendix 1: Suggested CWTP Workshop Modelled on My Touchstone Experiences

- Pre-preparation: invite participants to listen to this excellent BBC Radio 4 documentary, The Pebble in Your Pocket, https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000j21w

- Meet in a rocky outdoor place.

- Agree ground rules for the session’s Working Alliance (e.g., confidentiality and closing time). Share Nigel Gibbons’ acrostic ‘Writing Well’, encouraging participants to park their inner critics.

- Share some specific geological information about the location. (Is it sedimentary, igneous or metamorphic? Was it once a desert or under a sea?)

- Share some ‘Pebbly Quotes and Prompts’ (below) as a warm-up writing exercise, then come back together and share the results.

- Invite participants to spend at least 10 minutes finding a pebble, stone, or rock of choice—not writing, but just looking at it, being with it. Why not go and lie on the rocks and notice what one is experiencing / hearing / feeling. People enjoy this time and want longer. Write sentence stems ‘What I notice is...’

- Ask one’s rock, stone, or pebble some ‘who? what? when? where? why?’ questions and note what comes back. E. g.:

- Where are you from?

- Where are you going?

- Tell me about all the time in the world.

- What is your name?

- What languages do you speak?

- What are you scared of?

- What’s your earliest memory?

- Tell me a home truth.

- What do you dream of?

- Opportunity for a free write to capture some aspects of that experience, writing into answering some of those questions.

- Share Charles Simic’s poem ‘Stone’ (https://www.mindfulnessassociation.net/words-of-wonder/stone-charles-simic/), inviting participants to pick a line or image they like and to run with it for a 20-minute write.

- Come back into a circle and share.

- Close. Hopefully go forth reinvigorated as per Joanna Macy’s Active Hope spiral.

References

Gibbons, N. (2012). Writing for wellbeing and health: Some personal reflections. Journal of Holistic Health, 2(2), 8–11. https://bhma.org/wp-content/uploads/woocommerce_uploads/2017/06/JHH9.2_article02_.pdf

Appendix 2: Choice Pebbly Quotes & Prompts for Touchstone Workshops

- ‘Take a stone in your hand and close your fist around it—until it starts to beat, live, speak, and move.’ Sámi poet Nils-Aslak Valkeapää

- ‘A stone is a thought that the earth develops over inhuman time.’ ‘The Stone’ by Louise Erdrich is a short story published in The New Yorker.

- ‘I wish that I might be a thinking stone’ Wallace Stevens, a line from ‘Le Monocle de mon Oncle’ (1918).

- ‘Cores:5’ by Alyson Hallett (2020, p. 33):

- ‘Rocks are not nouns but verbs—visible evidence of processes: a volcanic eruption,... the growth of a mountain belt.’ Marcia Bjornerud (2018)

- Kenneth Koch (1994), ‘Aesthetics of Stone’

The gods take stone

And turn it into men and women;

Men and women take gods

And turn them into stone. - ‘Stones are mute teachers; they silence the observer, and the most valuable lesson we learn from them we cannot communicate.’—Goethe

stone

nest

stone

egg

stone

hatch

References

Bjornerud, M. (2018). Timefulness: How thinking like a geologist can help save the world. Princeton University

Press. Erdrich, L. (2019, September 2). The stone. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/09/09/the-stone

Hallett, A. (2020). Cores:5. Titled ground.

Koch, K. (1994). Aesthetics of stone. One train. Knopf.

Stevens, W. (1918/1990). Le monocle de mon oncle. The collected poems of Wallace Stevens. Knopf.

Valkeapää, N-A. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nils-Aslak_Valkeap%C3%A4%C3%A4

Volume 4, No. 1 | October 2024